From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Part of a series on |

| Antisemitism |

|---|

Part of Jewish history

|

| History · Timeline · Resources |

| Category |

| Part of a series on |

| Discrimination |

|---|

| General forms |

| Specific forms |

| Countermeasures |

| Discrimination portal |

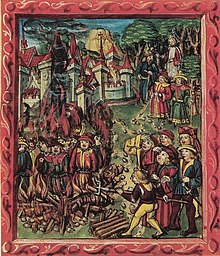

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is suspicion of, hatred toward, or discrimination against Jews for reasons connected to their Jewish heritage. Social scientists consider it a form of racism. In a 2005 U.S. governmental report, antisemitism is defined as "hatred toward Jews—individually and as a group—that can be attributed to the Jewish religion and/or ethnicity."[1] A person who holds such views is called an "antisemite". Antisemitism may be manifested in many ways, ranging from expressions of hatred of or discrimination against individual Jews to organized violent attacks by mobs, state police, or even military attacks on entire Jewish communities. Extreme instances of persecution include thepogroms which preceded the First Crusade in 1096, the expulsion from England in 1290, the massacres of Spanish Jews in 1391, the persecutions of the Spanish Inquisition, the expulsion from Spain in 1492, Cossack massacres in Ukraine, various pogroms in Russia, the Dreyfus affair, the Final Solution by Hitler's Germany, official Soviet anti-Jewish policies and the Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim countries.

While the term's etymology might suggest that antisemitism is directed against all Semitic peoples, the term was coined in the late 19th century in Germany as a more scientific-sounding term for Judenhass ("Jew-hatred"),[2] and that has been its normal use since then.[3]

######################################################

####################################################

######################################################

####################################################

Etymology

Although Wilhelm Marr is generally credited with coining the word anti-Semitism (see below), Alex Bein writes that the word was first used in 1860 by the Austrian Jewish scholar Moritz Steinschneider in the phrase "anti-Semitic prejudices".[12] Steinschneider used this phrase to characterize Ernest Renan's ideas about how "Semitic races" were inferior to "Aryan races." These pseudo-scientific theories concerning race, civilization, and "progress" had become quite widespread in Europe in the second half of the 19th century, especially as Prussian nationalistic historian Heinrich von Treitschke did much to promote this form of racism. He coined the term "the Jews are our misfortune" which would later be widely used by Nazis.[13] In Treitschke's writings Semitic was synonymous with Jewish, in contrast to its use by Renan and others.

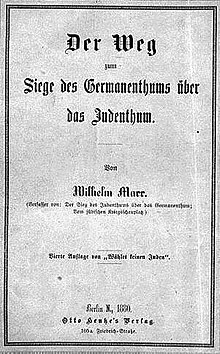

In 1873 German journalist Wilhelm Marr published a pamphlet "The Victory of the Jewish Spirit over the Germanic Spirit. Observed from a non-religious perspective." ("Der Sieg des Judenthums über das Germanenthum. Vom nicht confessionellen Standpunkt aus betrachtet.")[14] in which he used the word "Semitismus" interchangeably with the word "Judentum" to denote both "Jewry" (the Jews as a collective) and "jewishness" (the quality of being Jewish, or the Jewish spirit). Although he did not use the word "Antisemitismus" in the pamphlet, the coining of the latter word followed naturally from the word "Semitismus", and indicated either opposition to the Jews as a people, or else opposition to Jewishness or the Jewish spirit, which he saw as infiltrating German culture. In his next pamphlet, "The Way to Victory of the Germanic Spirit over the Jewish Spirit", published in 1880, Marr developed his ideas further and coined the related German word Antisemitismus – antisemitism, derived from the word "Semitismus" that he had earlier used.

The pamphlet became very popular, and in the same year he founded the "League of Antisemites" ("Antisemiten-Liga"), the first German organization committed specifically to combatting the alleged threat to Germany and German culture posed by the Jews and their influence, and advocating theirforced removal from the country.

So far as can be ascertained, the word was first widely printed in 1881, when Marr published "Zwanglose Antisemitische Hefte," and Wilhelm Schererused the term "Antisemiten" in the January issue of "Neue Freie Presse". The related word semitism was coined around 1885.

Definition

Though the general definition of antisemitism is hostility or prejudice against Jews, and, according to Olaf Blaschke, become an 'umbrella term for negative stereotypes about Jews,'[15] a number of authorities have developed more formal definitions.

Holocaust scholar and City University of New York professor Helen Fein defines it as "a persisting latent structure of hostile beliefs towards Jews as a collective manifested in individuals as attitudes, and in culture as myth, ideology, folklore and imagery, and in actions – social or legal discrimination, political mobilization against the Jews, and collective or state violence – which results in and/or is designed to distance, displace, or destroy Jews as Jews."

Elaborating on Fein's definition, Dietz Bering of the University of Cologne writes that, to antisemites, "Jews are not only partially but totally bad by nature, that is, their bad traits are incorrigible. Because of this bad nature: (1) Jews have to be seen not as individuals but as a collective. (2) Jews remain essentially alien in the surrounding societies. (3) Jews bring disaster on their 'host societies' or on the whole world, they are doing it secretly, therefore the antisemites feel obliged to unmask the conspiratorial, bad Jewish character."[16]

For Sonja Weinberg, as distinct from economic and religious anti-Judaism, antisemitism in its modern form shows conceptual innovation, a resort to 'science' to defend itself, new functional forms and organisational differences. It was anti-liberal, racialist and nationalist. It promoted the myth that Jews conspired to 'judaise' the world; it served to consolidate social identity; it channeled dissatisfactions among victims of the capitalist system; and it was used as a conservative cultural code to fight emancipation and liberalism.[17]

Bernard Lewis defines antisemitism as a special case of prejudice, hatred, or persecution directed against people who are in some way different from the rest. According to Lewis, antisemitism is marked by two distinct features: Jews are judged according to a standard different from that applied to others, and they are accused of "cosmic evil." Thus, "it is perfectly possible to hate and even to persecute Jews without necessarily being anti-Semitic" unless this hatred or persecution displays one of the two features specific to antisemitism.[18]

There have been a number of efforts by international and governmental bodies to define antisemitism formally. The U.S. Department of State defines antisemitism in its 2005 Report on Global Anti-Semitism as "hatred toward Jews—individually and as a group—that can be attributed to the Jewish religion and/or ethnicity."[1]

In 2005, the European Monitoring Centre on Racism and Xenophobia (now Fundamental Rights Agency), then an agency of the European Union, developed a more detailed working definition, which states: "Antisemitism is a certain perception of Jews, which may be expressed as hatred toward Jews. Rhetorical and physical manifestations of antisemitism are directed toward Jewish or non-Jewish individuals and/or their property, toward Jewish community institutions and religious facilities." It adds "such manifestations could also target the state of Israel, conceived as a Jewish collectivity." It provides contemporary examples of antisemitism, which include: promoting the harming of Jews in the name of an ideology or religion; promoting negative stereotypes of Jews; holding Jews collectively responsible for the actions of an individual Jewish person or group; denying the Holocaust or accusing Jews or Israel of exaggerating it; and accusing Jews of dual loyalty or a greater allegiance to Israel than their own country. It also lists ways in which attacking Israel could be antisemitic, and that denying the Jews their right to self-determination is anti-Semitic, e.g. by claiming that the existence of a state of Israel is a racist endeavor, or applying double standards by requiring of Israel a behavior not expected or demanded of any other democratic nation, or holding Jews collectively responsible for actions of the State of Israel.[19]

Evolution of usage

In 1879, Wilhelm Marr founded the Antisemiten-Liga (Antisemitic League). Identification with antisemitism and as an antisemite was politically advantageous in Europe in the latter 19th century. For example, Karl Lueger, the popular mayor of fin de siècle Vienna, skillfully exploited antisemitism as a way of channeling public discontent to his political advantage.[20] In its 1910 obituary of Lueger, The New York Times notes that Lueger was "Chairman of the Christian Social Union of the Parliament and of the Anti-Semitic Union of the Diet of Lower Austria.[21] In 1895 A. C. Cuza organized the Alliance Anti-semitique Universelle in Bucharest. In the period before World War II, when animosity towards Jews was far more commonplace, it was not uncommon for a person, organization, or political party to self-identify as an antisemite or antisemitic.

In 1882, the early Zionist pioneer Judah Leib Pinsker wrote that antisemitism was an inherited predisposition:

Judeophobia is a psychic aberration. As a psychic aberration it is hereditary, and as a disease transmitted for two thousand years it is incurable.' ... 'In this way have Judaism and Anti-Semitism passed for centuries through history as inseparable companions.'... ...'Having analyzed Judeophobia as an hereditary form of demonopathy, peculiar to the human race, and having represented Anti-Semitism as proceeding from an inherited aberration of the human mind, we must draw the important conclusion that we must give' up contending against these hostile impulses as we must against every other inherited predisposition.[22]

In the aftermath of the Kristallnacht pogrom in 1938, German propaganda minister Goebbels announced: "The German people is anti-Semitic. It has no desire to have its rights restricted or to be provoked in the future by parasites of the Jewish race."[23]

After the 1945 victory of the Allies over Nazi Germany, and particularly after the extent of the Nazi genocide of Jews became known, the term "antisemitism" acquired pejorative connotations. This marked a full circle shift in usage, from an era just decades earlier when "Jew" was used as a pejorative term.[24][25] Yehuda Bauer wrote in 1984: "There are no antisemites in the world... Nobody says, 'I am antisemitic.'" You cannot, after Hitler. The word has gone out of fashion."[26]

Forms

It is often emphasized that there are different forms of antisemitism. René König mentions social antisemitism, economic antisemitism, religious antisemitism, and political antisemitism as examples. König points out that these different forms demonstrate that the "origins of antisemitic prejudices are rooted in different historical periods." König asserts that differences in the chronology of different antisemitic prejudices and the irregular distribution of such prejudices over different segments of the population create "serious difficulties in the definition of the different kinds of antisemitism."[27] These difficulties may contribute to the existence of different taxonomies that have been developed to categorize the forms of antisemitism. The forms identified are substantially the same; it is primarily the number of forms and their definitions that differ. Bernard Lazare identifies three forms of antisemitism:Christian antisemitism, economic antisemitism, and ethnologic antisemitism.[28] William Brustein names four categories: religious, racial, economic and political.[29] The Roman Catholic historian Edward Flannery distinguished four varieties of antisemitism:[30][page needed]

- political and economic antisemitism, giving as examples Cicero and Charles Lindbergh;

- theological or religious antisemitism, sometimes known as anti-Judaism;

- nationalistic antisemitism, citing Voltaire and other Enlightenment thinkers, who attacked Jews for supposedly having certain characteristics, such as greed and arrogance, and for observing customs such as kashrut and Shabbat;

- and racial antisemitism, with its extreme form resulting in the Holocaust by the Nazis.

Louis Harap separates "economic antisemitism" and merges "political" and "nationalistic" antisemitism into "ideological antisemitism". Harap also adds a category of "social antisemitism".[31]

- religious (Jew as Christ-killer),

- economic (Jew as banker, usurer, money-obsessed),

- social (Jew as social inferior, "pushy," vulgar, therefore excluded from personal contact),

- racist (Jews as an inferior "race"),

- ideological (Jews regarded as subversive or revolutionary),

- cultural (Jews regarded as undermining the moral and structural fiber of civilization).

Cultural antisemitism

Louis Harap defines cultural antisemitism as "that species of anti-Semitism that charges the Jews with corrupting a given culture and attempting to supplant or succeeding in supplanting the preferred culture with a uniform, crude, "Jewish" culture.[32] Similarly, Eric Kandel characterizes cultural antisemitism as being based on the idea of “Jewishness” as a "religious or cultural tradition that is acquired through learning, through distinctive traditions and education." According to Kandel, this form of antisemitism views Jews as possessing "unattractive psychological and social characteristics that are acquired through acculturation."[33] Niewyk and Nicosia characterize cultural antisemitism as focusing on and condemning "the Jews' aloofness from the societies in which they live."[34] An important feature of cultural antisemitism is that it considers the negative attributes of Judaism to be redeemable by education or religious conversion.[35]

Religious antisemitism

Religious antisemitism is also known as anti-Judaism. Under this version of antisemitism, attacks would often stop if Jews stopped practicing or changed their public faith, especially byconversion to the official or right religion, and sometimes, liturgical exclusion of Jewish converts (the case of Christianized Marranos or Iberian Jews in the late 15th century and 16th century convicted of secretly practising Judaism or Jewish customs).[36]

Although the origins of antisemitism are rooted in the Judeo-Christian conflict, religious antisemitism, other forms of antisemitism have developed in modern times. Frederick Schweitzer asserts that, "most scholars ignore the Christian foundation on which the modern antisemitic edifice rests and invoke political antisemitism, cultural antisemitism, racism or racial antisemitism, economic antisemitism and the like."[37] William Nichols draws a distinction between religious antisemitism and modern antisemitism based on racial or ethnic grounds: "The dividing line was the possibility of effective conversion . . . a Jew ceased to be a Jew upon baptism." From the perspective of racial antisemitism, however, "... the assimilated Jew was still a Jew, even after baptism ... . From the Enlightenment onward, it is no longer possible to draw clear lines of distinction between religious and racial forms of hostility towards Jews... Once Jews have been emancipated and secular thinking makes its appearance, without leaving behind the old Christian hostility towards Jews, the new term antisemitism becomes almost unavoidable, even before explicitly racist doctrines appear."

No comments:

Post a Comment